Foibe massacres

Details

Locations of some of the foibe | |

| Location | Julian March, Kvarner, Dalmatia (Italy and Yugoslavia) |

|---|---|

| Date | 1943-1945 |

| Target |

|

Attack type | State terrorism, Ethnic cleansing (disputed) |

| Deaths | Estimates range from 3,000 to 5,000 killed; according to other sources 11,000. |

| Perpetrators | Croat and Slovene civilians, Yugoslav Partisans, OZNA |

Sources

Foibe massacres

Introduction

| Part of a series on |

| Aftermath of World War II in Yugoslavia |

|---|

| Main events |

| Massacres |

| Camps |

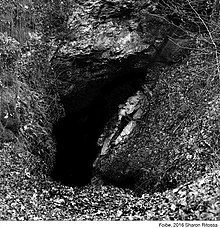

The foibe massacres, or simply the foibe, refers to mass killings both during and after World War II, mainly committed by Yugoslav Partisans against the local ethnic Italian population (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), mainly in Julian March, Istria, Kvarner, and Dalmatia. The term refers to the victims who were often thrown alive into foibas (deep natural sinkholes; by extension, it also was applied to the use of mine shafts, etc., to hide the bodies). In a wider or symbolic sense, some authors used the term to apply to all disappearances or killings of Italian people in the territories occupied by Yugoslav forces. They excluded possible 'foibe' killings by other parties or forces. Others included deaths resulting from the forced deportation of Italians, or those who died while trying to flee from these contested lands.

The estimated number of people killed in Trieste is disputed, varying from hundreds to thousands. The Italian historian, Raoul Pupo estimates 3,000 to 4,000 total victims, across all areas of former Yugoslavia and Italy from 1943 to 1945, with the primary target being military and repressive forces of the Fascist regime, and civilians associated with the regime, including Slavic collaborators. He places the events in the broader context of "the collapse of a structure of power and oppression: that of the fascist state in 1943, that of the Nazi-fascist state of the Adriatic coast in 1945." The events were also part of larger reprisals in which tens-of-thousands of Slavic collaborators of Axis forces were killed in the aftermath of WWII, following a brutal war in which some 800,000 Yugoslavs, the vast majority civilians, were killed by Axis occupation forces and collaborators.

Origin and meaning of the term

The name was derived from a local geological feature, a type of deep karst sinkhole called foiba. The term includes by extension killings and "burials" in other subterranean formations, such as the Basovizza "foiba", which is a mine shaft.

In Italy the term foibe has, for some authors and scholars, taken on a symbolic meaning; for them it refers in a broader sense to all the disappearances or killings of Italian people in the territories occupied by Yugoslav forces. According to author Raoul Pupo:

"It is well known that the majority of the victims didn't end their lives in a Karst cave, but met their deaths on the road to deportation, as well as in jails or in Yugoslav concentration camps."

Pupo also notes:

"With regard to the civilian population of Venezia Giulia the Yugoslav troops did not behave at all like an army occupying enemy territory: nothing in their actions recalls the indiscriminate violence of Red Army soldiers in Germany, on the contrary, their discipline seems in some ways superior even to that of the Anglo-American units."

Raoul Pupo states that the primary targets of the purges were ideological, i.e. military and repressive forces of the Fascist regime and their supporters, and included suspected Slavic collaborators. Thus he writes the victims were not targeted for being “Italian”, contradicting those on the Italian right who seek to present this as an “ethnic cleansing”, and exploit the events politically. The terror spread by these disappearances and killings eventually caused the majority of the Italians of Istria, Rijeka, and Zadar to flee to other parts of Italy or the Free Territory of Trieste. According to Fogar and Miccoli there is

"the need to put the episodes in 1943 and 1945 within [the context of] a longer history of abuse and violence, which began with Fascism and with its policy of oppression of the minority Slovenes and Croats and continued with the Italian aggression on Yugoslavia, which culminated with the horrors of the Nazi-Fascist repression against the Partisan movement."

Other authors assert that the post-war pursuit of the 'truth' of the foibe, as a means of transcending Fascist/Anti-Fascist oppositions and promoting popular patriotism, has not been the preserve of right-wing or neo-Fascist groups. Evocations of the 'Slav other' and of the terrors of the foibe made by state institutions, academics, amateur historians, journalists, and the memorial landscape of everyday life were the backdrop to the post-war renegotiation of Italian national identity.

Gaia Baracetti notes that Italian representations of foibe, such as a miniseries on national television, are replete with historical inaccuracies and stereotypes, portraying Slavs as “merciless assassins”, similar to fascist propaganda, while “largely ignoring the issue of Italian war crimes” Others, including members of Italy's Jewish community, have objected to Italian right-wing efforts to equate the foibe with the Holocaust, via historical distortions which include exaggerated foibe victim claims, in an attempt to turn Italy from a perpetrator in the Holocaust, to a victim.

Events

The first (disputed) claims of people being thrown into foibe date to 1943, after the Wehrmacht took back the area from the Partisans. Other authors claimed the 70 hostages were killed and burned in the Nazi lager of the Risiera of San Sabba, on 4 April 1944.

The massacres occurred in two waves, the first taking places in the interlude between the Armistice of Cassibile and the German occupation of Istria in September 1943, and the second after the Yugoslav occupation of the region in May 1945. Victims of the first wave numbered in the hundreds, whereas those of the second wave in the thousands. The first wave of killings is widely regarded as a disorganized, spontaneous series of revenge killings by Slovenes and Croats after twenty years of Fascist oppression, as well as "jacquerie" against Italian landowners and more broadly the Italian elite in the region; these killings targeted members of the Fascist Party, their relatives (as in the famous case of Norma Cossetto), Italian landowners, policemen and civil servants of all ranks, considered as symbols of Italian oppression. The scope and nature of the second wave is much more disputed; Slovene and Croat historians, as well as Communist-leaning Italian historians such as Alessandra Kersevan and Claudia Cernigoi, characterize it as another wave of revenge killings against Fascist collaborators and members of the armed forces of the Italian Social Republic, whereas Italian historians such as Raoul Pupo, Gianni Oliva and Roberto Spazzali argue that this was the result of a deliberate Titoist policy aimed at spreading terror among the Italian population of the region and eliminating anyone who opposed Yugoslav plans of annexing Istria and the Julian March, including anti-Fascists. It is to be noted that while the foibe became the symbol of these massacres, only a minority of the victims were killed with this method, largely during the first wave; a far larger part were executed and buried in mass graves or died in Yugoslav prisons and concentration camps.

After the re-occupation of Istria by Axis forces in September 1943, following the first wave of killings, the fire brigade of Pola, under the command of Arnaldo Harzarich, recovered 204 bodies from the foibe of the region. Between 1945 and 1948, Italian authorities recovered a total 369 corpses from foibe in the Italian-controlled part of the Free Territory of Trieste (Zone A), and another 95 were recovered from mass graves in the same area; these included also bodies of German soldiers killed in the closing days of the war and hastily buried in these cavities. Foibe located in the Yugoslav-controlled part of the Free Territory of Trieste, as well as in the rest of Istria, were never searched as this territory was now under Yugolav control. Great controversy has surrounded the foiba of Basovizza, one of the most famous foibe (and unlikely called as such, as it was not a natural foiba but a disused mine shaft). Newspaper reports from the postwar era claimed anywhere from 18 to 3,000 victims in this foiba alone, but Trieste authorities refused to fully excavate it, citing financial constraints. At the end of the war, local villagers had thrown the bodies of dead German soldiers (killed in a battle fought in the vicinity in the closing days of the war) and horses into the mine shaft, which after the war had also been used as a garbage dump by the authorities of the Free Territory of Trieste. After the war the Basovizza foibe was used by the Italian authorities as a garbage dump. Thus no Italian victims were ever recovered or determined at Basovizza. In 1959 the pit was sealed and a monument erected, which later became the central site for the annual foibe commemorations.

In 1947, British envoy W. J. Sullivan wrote of Italians arrested and deported by Yugoslav forces from around Trieste: "there is little doubt, while some of the persons deported may have been innocent, others were undoubtedly active fascists with more than mere party memberships on their conscience. Some of these have returned to Trieste but have kept well out of the Allied authorities, not participating in enquiries about the deportations for fear of arrest and trial 'for their former fascist activities'." Alongside a large number of Fascists, however, among those killed were also anti-Fascists who opposed the Yugoslav annexation of the region, such as Socialist Licurgo Olivi and Action Party leader Augusto Sverzutti, members of the Committee of National Liberation of Gorizia; in Trieste, the same fate befell Resistance leaders Romano Meneghello (posthumously awarded a Silver Medal of Military Valor for his Resistance activities) and Carlo Dell'Antonio. In Fiume (where at least 652 Italians were killed or disappeared between 3 May 1945 and 31 December 1947, according to a joint Italian-Croat study), Autonomist Party leaders Mario Blasich, Joseph Sincich and Nevio Skull were among those executed by the Yugoslavs soon after the occupation, as was anti-Fascist and Dachau survivor Angelo Adam. Priests were also targeted by the new Yugoslav Communist authorities, as in the case of Francesco Bonifacio. Out of 1,048 people who were arrested and executed by the Yugoslavs in the province of Gorizia in May 1945, according to a list drafted by a joint Italian-Slovene commission in 2006, 470 were members of the military or police forces of the Italian Social Republic, 110 were Slovene civilians accused of collaborationism, and 320 were Italian civilians.

Number of victims

The number of those killed or left in foibe during and after the war is still unknown; it is difficult to establish and a matter of controversy. Estimates range from hundreds to twenty thousand. According to data gathered by a joint Slovene-Italian historical commission established in 1993, "the violence was further manifested in hundreds of summary executions - victims were mostly thrown into the Karst chasms (foibe) - and in the deportation of a great number of soldiers and civilians, who either wasted away or were killed during the deportation".

Historians Raoul Pupo and Roberto Spazzali, have estimated the total number of victims at about 5,000, and note that the targets were not "Italians", but military and repressive forces of the Fascist regime, and civilians associated with the regime. More recently, Pupo has revised the total victims estimates to 3,000 to 4,000. Italian historian Guido Rumici estimated the number of Italians executed, or died in Yugoslav concentration camps, as between 6,000 and 11,000, while Mario Pacor estimated that after the armistice about 400-500 people were killed in the foibe and about 4,000 were deported, many of whom were later executed.

It was not possible to extract all the corpses from the foibe, some of which are deeper than several hundred meters; some sources are attempting to compile lists of locations and possible victim numbers. Between October and December 1943, the Fire brigade of Pola, helped by mine workers, recovered a total of 159 victims of the first wave of mass killings from the foibe of Vines (84 bodies), Terli (26 bodies), Treghelizza (2 bodies), Pucicchi (11 bodies), Villa Surani (26 bodies), Cregli (8 bodies) and Carnizza d'Arsia (2 bodies); another 44 corpses were recovered in the same period from two bauxite mines in Lindaro and Villa Bassotti. More bodies were sighted, but not recovered.

The most famous Basovizza foiba, was investigated by English and American forces, starting immediately on June 12, 1945. After 5 months of investigation and digging, all they found in the foiba were the remains of 150 German soldiers and one civilian killed in the final battles for Basovizza on April 29–30, 1945. The Italian mayor, Gianni Bartoli continued with investigations and digging until 1954, with speleologists entering the cave multiple time, yet they found nothing. Between November 1945 and April 1948, firefighters, speleologists and policemen inspected foibe and mine shafts in the "Zone A" of the Free Territory of Trieste (mainly consisting in the surroundings of Trieste), where they recovered 369 corpses; another 95 were recovered from mass graves in the same area. At the time, no inspections were carried out either in the Yugoslav-controlled "Zone B", or in the rest of Istria.

Other foibe and mass graves were investigated in more recently in Istria and elsewhere in Slovenia and Croatia; for instance, human remains were discovered in the Idrijski Log foiba near Idrija, Slovenia, in 1998; four skeletons were found in the foiba of Plahuti near Opatija in 2002; in the same year, a mass grave containing the remains of 52 Italians and 15 Germans, most likely all military, was discovered in Slovenia, not far from Gorizia; in 2005, the remains of about 130 people killed between the 1940s and the 1950s were recovered from four foibe located in northeastern Istria.

Background

Ancient times

Evidence of Italic people living alongside those from other ethnic groups on the eastern side of the Adriatic as far north as the Alps goes back at least to the Bronze Age, and the populations have been mixed ever since. A 2001 population census counted 23 languages spoken by the people of Istria.

Dalmatia is named after the Dalmatae, an Illyrian tribe. The region was conquered and subjugated by Rome after more than 120 years of the Roman-Dalmatae Wars, and later uprisings against Roman rule. It then became the Roman province of Dalmatia. In the 7th century Slavic tribes started arriving in the area. In 951 the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII described Dalmatia as consisting of Slavic lands, with the Kingdom of Croatia in northern Dalmatia, and the South Slavic states of Pagania, Zachumlia, Travunija and Duklja occupying southern Dalmatia.

Via conquests, the Republic of Venice, between the 9th century and 1797, extended its dominion to Istria, the islands of Kvarner and Dalmatia. From the Middle Ages onwards numbers of Slavic people near and on the Adriatic coast were ever increasing, due to their expanding population and due to pressure from the Turks pushing them from the south and east. This led to Italic people becoming ever more confined to urban areas, while the countryside was populated by Slavs, with certain isolated exceptions. In particular, the population was divided into urban-coastal communities (mainly Romance speakers) and rural communities (mainly Slavic speakers), with small minorities of Morlachs and Istro-Romanians.

Republic of Venice influenced the neolatins of Istria and Dalmatia until 1797, when it was conquered by Napoleon: Capodistria and Pola were important centers of art and culture during the Italian Renaissance. From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, Italian and Slavic communities in Istria and Dalmatia had lived peacefully side by side because they did not know the national identification, given that they generically defined themselves as "Istrians" and "Dalmatians", of "Romance" or "Slavic" culture.

Austrian Empire

After the fall of Napoleon (1814), Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia were annexed to the Austrian Empire. Many Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento movement that fought for the unification of Italy. However, after the Third Italian War of Independence (1866), when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom Italy, Istria and Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic. This triggered the gradual rise of Italian irredentism among many Italians in Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia, who demanded the unification of the Julian March, Kvarner and Dalmatia with Italy. The Italians in Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia supported the Italian Risorgimento: as a consequence, the Austrians saw the Italians as enemies and favored the Slav communities of Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia, fostering the nascent nationalism of Slovenes and Croats.

During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:

Her Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard. His Majesty calls the central offices to the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.

— Franz Joseph I of Austria, Council of the Crown of 12 November 1866

Historians note that while Slavs made up 80-95% of the Dalmatia populace, only Italian language schools existed until 1848, and due to restrictive voting laws, the Italian-speaking minority retained political control of Dalmatia, keeping Italian as the only official language. Only after Austria liberalized elections in 1870, allowing more majority Slavs to vote, did Croatian parties gain control. Croatian finally became an official language in Dalmatia in 1883, along with Italian. Yet minority Italian-speakers continued to wield strong influence, since Austria favored Italians for government work, thus in the Austrian capital of Dalmatia, Zara, the proportion of Italians continued to grow, making it the only Dalmatian city with an Italian majority.

In the 1910 Austro-Hungarian census, Istria had a population of 57.8% Slavic-speakers (Croat and Slovene), and 38.1% Italian speakers. For the Austrian Kingdom of Dalmatia, (i.e. Dalmatia), the 1910 numbers were 96.2% Slavic speakers and 2.8% Italian speakers, recording a drastic decline in the number of Dalmatian Italians, who in 1845 amounted to 20% of the total population of Dalmatia. In 1909 the Italian language lost its status as the official language of Dalmatia in favor of Croatian only (previously both languages were recognized): thus Italian could no longer be used in the public and administrative sphere.

When Italy took over the Veneto region, it sought to repress the language of the local Slovene minority. In 1911, complaining of local Italian efforts to falsely count Slovenes as Italians, the Trieste Slovene newspaper Edinost wrote: “We are here, we want to stay here and enjoy our rights! We throw the ruling clique the glove a duel, and we will not give up until artificial Trieste Italianism is crushed in dust, lying under our feet.” Due to these complaints, Austria carried a census recount, and the number of Slovenes increased by 50-60% in Trieste and Gorizia, proving Slovenes were initially falsely counted as Italians.

After World War I

To get Italy to join the Triple Entente in WWI, the secret 1915 Treaty of London promised Italy Istria and parts of Dalmatia, German-speaking South Tyrol, the Greek Dodecanese Islands, parts of Albania and Turkey, plus more territory for Italy's North Africa colonies.

After World War I, the whole of the former Austrian Julian March, including Istria, and Zadar in Dalmatia were annexed by Italy, while Dalmatia (except Zadar) was annexed by the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Contrary to the Treaty of London, in 1919 Gabrielle D’Annunzio led an army of 2,600 Italian war veterans to seize the city of Fiume (Rijeka). D’Annunzio created the Italian Regency of Carnaro, with him as its dictator, or Comandante, and a constitution foreshadowing the Fascist system. After D’Annuzio's removal, Fiume briefly become a Free State, but local Fascists in 1922 carried out a coup, and in 1924 Italy annexed Fiume.

As a result, 480,000 Slavic-speakers came under Italian rule, while 12,000 Italian speakers were left in Yugoslavia, mostly in Dalmatia. Italy began a policy of forced Italianization. which intensified under Fascist rule from 1922 to 1943. Italy forbade Slavic languages in public institutions and schools, moved 500 Slovene teachers to the interior of Italy, replacing them with Italian ones, the government changed people’s names to Italian ones, Slavic cultural, sporting and political associations were banned. As a result, 100,000 Slavic speakers left Italian areas in an exodus, moving mostly to Yugoslavia. In Fiume alone, the Slavic population declined by 66% by 1925, compared to pre-WWI levels. The remnants of the Italian community in Dalmatia (which had started a slow but steady emigration to Istria and Venice during the 19th century) left their cities toward Zadar and the Italian mainland.

During the early 1920s, nationalistic violence was directed both against the Slovene and Croat minorities in Istria (by Italian nationalists and Fascists) and the Italian minority in Dalmatia (by Slovene and Croat nationalists). In Dalmatia hostilies arose when in 1918 Italy occupied by force several cities, like Šibenik, with large majority Slav populations, while armed Italian nationalist irregulars commanded by Dalmatian Italian Count Fanfogna proceeded further south to Split. This led to the 1918–20 unrest in Split, when members of the Italian minority and their properties were assaulted by Croatian nationalists (and two Italian Navy personnel and a Croatian civilian were later killed during riots). In 1920 Italian nationalists and fascists burned the Trieste National Hall, the main center of the Slovene minority in Trieste. During D’Annunzio’s armed 1919-1920 occupation of Fiume, hundreds of mostly non-Italians were arrested, including many leaders of the Slavic community, and thousands of Slavs started to flee the city, with additional anti-Slav violence during the 1922 Fascist coup,.

In a 1920 speech in Pola (Pula) Istria, Benito Mussolini proclaimed an expansionist policy, based on the fascist concept of spazio vitale, similar to the Nazi lebensraum policy:

Towards expansion in the Mediterranean and in the East, Italy is driven by demographic factors. But to realize the Mediterranean dream, the Adriatic, which is our gulf, must be in our hands. When dealing with such a race as Slavic - inferior and barbaric - we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy. We should not be afraid of new victims. The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps. I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians.

— Benito Mussolini, speech held in Pula, 20 September 1920

With Fascist Italy’s imperialistic policy of spanning the Mediterranean, Italy in 1927 signed an agreement with the Croatian fascist, terrorist Ustaše organization, under which contingent on their seizing power, the Ustaše agreed to cede to Italy additional territory in Dalmatia and the Bay of Kotor, while also renouncing all Croatian claims to Istria, Rijeka, Zadar and the Adriatic Islands, which Italy annexed after WWI. The Ustaše became a tool of Italy. They embarked on a terrorist campaign of placing bombs on international trains bound for Yugoslavia, and instigated an armed uprising in Lika, then part of Yugoslavia. In 1934 in Marseille, the Italy-supported Ustaše assassinated King Alexander I of Yugoslavia, while simultaneously killing the French Foreign Minister.

World War II

Seeking to create an Imperial Italy, Mussolini started expansionist wars in the Mediterranean, with Fascist Italy invading and occupying Albania in 1939, and in 1940 France, Greece, Egypt, and the Malta. In April 1941, Italy and its Nazi Germany ally, attacked Yugoslavia. They carved up Yugoslavia, with Italy occupying large portions of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Serbia and Macedonia, directly annexing to Italy Ljubljana Province, Gorski Kotar and Central Dalmatia, along with most Croatian islands.

To suppress the mounting resistance led by the Partisans, the Italians adopted tactics of "summary executions, hostage-taking, reprisals, internments and the burning of houses and villages.". The Italian government sent tens of thousands of Croat and Slovene civilians, among them many women and children, to Italian concentration camps , such as Rab, Gonars, Monigo, Renicci, Molat, Zlarin, Mamula, etc. Thousands died in the camps, including hundreds of children. Italian forces executed thousands of additional civilians as hostages and conducted massacres, such as the Podhum massacre in 1942. On their own, or with their Nazi and collaborationist allies, the Italian army undertook brutal anti-Partisan offensives, during which tens-of-thousands of Partisans were killed, along with many civilians, plus thousands more civilians executed or sent to concentration camps following the campaigns. From Ljubljana Province alone, historians estimate the Italians sent 25,000 to 40,000Slovenes to concentration camps, which represents 8-12% of the total population.

No Italians were ever brought to trial for war crimes committed in Yugoslavia or elsewhere. In 1944, near the end of a war in which Nazis, Fascists and their allies killed over 800,000 Yugoslavs, Croat poet Vladimir Nazor wrote: "We will wipe away from our territory the ruins of the destroyed enemy tower, and we will throw them in the deep sea of oblivion. In the place of a destroyed Zara, a new Zadar will be reborn, and this will be our revenge in the Adriatic". (Zara had been under Fascist rule for 22 years, and was in ruins because of heavy Allied bombing).

Investigations

After the war, inspector Umberto de Giorgi, who was State Police marshal under fascist and Nazi rule, led the Foibe Exploration Team. Between 1945 and 1948 they investigated 71 foibe locations on the Italian side of the border. 23 of these were empty, in the rest they discovered some 464 corpses. These included soldiers killed during the last battles of the war. Among the 246 identified corpses, more than 200 were military (German, Italian, other), and some 40 were civilians, of the latter, 30 killed after the war.

Due to claims of hundreds having been killed and tossed into the Basovizza mineshaft, in August–October, 1945 British military authorities investigated the shaft, ultimately recovering 9 German soldiers, 1 civilian and a few horse cadavers. Based on these results the British suspended excavations. Afterwards the city of Trieste used the mineshaft as a garbage dump. Despite repeat demands from various right-wing groups to further excavate the shaft, the government of Trieste, led by the Christian Democratic mayor Gianni Bartoli, declined to do so, claiming among other reasons, lack of financial resources. In 1959 the shaft was sealed and a monument erected, thus becoming the center of the annual foibe commemorations.

Only a few trials were held, including that of the Trieste Zoll-Steffe criminal gang, for the killing of 18 people in the Plutone foibe in May 1945. Afterwards, Yugoslav authorities arrested the gang members and took them to Ljubljana, with two killed along the way while trying to escape, and the others convicted before a military tribunal. Additional members of the gang were brought before an Italian court in Trieste 1947, and were convicted and sentenced to prison for 2–3 years for their role in the Plutone killings

In 1949 a trial was held in Trieste for those accused of killing Mario Fabian, a torturer in the “Collotti gang”, a fascist squad that during the war killed and tortured Slovene and Italian antifascists, and Jews. Fabian was taken from his home on May 4, 1945, then shot and tossed into the Basovizza shaft. He is the only known Italian victim of Basovizza. His executioners were at first condemned, but later acquitted. The historian Pirjevec notes that the head of the gang, Gaetano Collotti, was awarded a medal by the Italian government in 1954, for fighting Slovene partisans in 1943, despite the fact that Collotti and his gang had committed many crimes while working for the Gestapo, and was killed by Italian partisans near Treviso in 1945.

In 1993 a study titled Pola Istria Fiume 1943-1945 by Gaetano La Perna provided a detailed list of the victims of Yugoslav occupation (in September–October 1943 and from 1944 to the very end of the Italian presence in its former provinces) in the area. La Perna gave a list of 6,335 names (2,493 military, 3,842 civilians). The author considered this list "not complete".

A 2002 joint report by Rome's Society of Fiuman studies (Società di Studi Fiumani) and Zagreb's Croatian Institute of History (Hrvatski institut za povijest) concluded that from Rijeka and the surrounding area "no less than 500 persons of Italian nationality lost their lives between 3 May 1945 and 31 December 1947. To these we should add an unknown number of 'missing' (not less than a hundred) relegated into anonymity due to missing inventory in the Municipal Registries together with the relevant number of victims having (...) Croatian nationality (who were often, at least between 1940 and 1943, Italian citizens) determined after the end of war by the Yugoslav communist regime."

In March 2006, the border municipality of Nova Gorica in Slovenia released a list of names of 1,048 citizens of the Italian city of Gorizia (the two cities belonged until the Treaty of Paris of 1947 to the same administrative body) who disappeared in May 1945 after being arrested by the Partisan 9th Corps. According to the Slovene government, "the list contains the names of persons arrested in May 1945 and whose destiny cannot be determined with certainty or whose death cannot be confirmed".

Alleged motives

It has been alleged that the killings were part of a purge aimed at eliminating potential enemies of communist Yugoslav rule, which would have included members of German and Italian fascist units, Italian officers and civil servants, parts of the Italian elite who opposed both communism and fascism (including the leadership of Italian anti-fascist partisan organizations and the leaders of Fiume's Autonomist Party, including Mario Blasich and Nevio Skull), Slovenian and Croatian anti-communists, collaborators and radical nationalists.

Another reason for the killings was retribution for the years of Italian repression, forced Italianization, suppression of Slavic sentiments and killings performed by Italian authorities during the war, not just in the concentration camps (such as Rab and Gonars), but also in reprisals often undertaken by the fascists.

Pamela Ballinger in her book, History in Exile: Memory and Identity at the Borders of the Balkans, wrote:

I heard exiles' accounts of "Slavic barbarity" and "ethnic cleansing," suffered in Istria between 1943 and 1954, as well as Slovene and Croat narratives of the persecution experienced under the fascist state and at the hands of neofascists in the postwar period. Admittedly, I could not forget--as many exiles seemed to do--that the exodus from Istria followed on twenty years of the fascistization and Italianization of Istria, as well as a bloody Italian military campaign in Yugoslavia between 1941 and 1943. Nor could I countenance some exiles' frequent expressions of anti-Slav chauvinism. At the same time, however, I could not accept at face value the claim by some that the violence the Slavs suffered under fascism justified subsequent events in Istria or that all those who left Istria were compromised by fascism. Similarly, I came to reject the argument that ethno-national antagonism had not entered into the equation, as well as the counterview that the exodus represented simply an act of "ethnic cleansing".

The report by the mixed Italian-Slovenian commission describes the circumstances of the 1945 killings as follows:

14. These events were triggered by the atmosphere of settling accounts with the fascist violence; but, as it seems, they mostly proceeded from a preliminary plan which included several tendencies: endeavours to remove persons and structures who were in one way or another (regardless of their personal responsibility) linked with Fascism, with Nazi supremacy, with collaboration and with the Italian state, and endeavours to carry out preventive cleansing of real, potential or only alleged opponents of the communist regime, and the annexation of the Julian March to the new Yugoslavia. The initial impulse was instigated by the revolutionary movement which was changed into a political regime, and transformed the charge of national and ideological intolerance between the partisans into violence at national level.

Post-War

The foibe have been a neglected subject in mainstream political debate in Italy, Yugoslavia and former-Yugoslav nations, only recently garnering attention with the publication of several books and historical studies. It is thought that after World War II, while Yugoslav politicians rejected any alleged crime, Italian politicians wanted to direct the country's attention toward the future and away from the idea that Italy was, in fact, a defeated nation.

So, the Italian government tactically "exchanged" the impunity of the Italians accused by Yugoslavia for the renunciation to investigate the foibe massacres. Italy never extradited or prosecuted some 1,200 Italian Army officers, government officials or former Fascist Party members accused of war crimes by Yugoslavia, Ethiopia, Greece and other occupied countries and remitted to the United Nations War Crimes Commission. On the other hand, Belgrade didn't insist overmuch on requesting the prosecution of alleged Italian war criminals.

Re-emergence of the issue

For several Italian historians these killings were the beginning of organized ethnic cleansing. Silvio Berlusconi's coalition government brought the issue back into open discussion: the Italian Parliament (with the support of the vast majority of the represented parties) made February 10 National Memorial Day of the Exiles and Foibe, first celebrated in 2005 with exhibitions and observances throughout Italy (especially in Trieste). The occasion is held in memory of innocents killed and forced to leave their homes, with little support from their home country. In Carlo Azeglio Ciampi's words: Time has come for thoughtful remembrance to take the place of bitter resentment. Moreover, for the first time, leaders from the Italian Left, such as Walter Veltroni, visited the Basovizza foiba and admitted the culpability of the Left in covering up the subject for decades.

Nowadays, a large part of the Italian Left acknowledges the nature of the foibe massacres, as attested by some declarations of Luigi Malabarba, Senator for the Communist Refoundation Party, during the parliamentary debate on the institution of the National Memorial Day: "In 1945 there was a ruthless policy of exterminating opponents. Here, one must again recall Stalinism to understand what Tito's well-organized troops did. (...) Yugoslav Communism had deeply assimilated a return to nationalism that was inherent to the idea of 'Socialism in One Country'. (...) The war, which had begun as anti-fascist, became anti-German and anti-Italian."

Italian president Giorgio Napolitano took an official speech during celebration of the "Memorial Day of Foibe Massacres and Istrian-Dalmatian exodus" in which he stated:

...Already in the unleashing of the first wave of blind and extreme violence in those lands, in the autumn of 1943, summary and tumultuous justicialism, nationalist paroxysm, social retaliation and a plan to eradicate Italian presence intertwined in what was, and ceased to be, the Julian March. There was therefore a movement of hate and bloodthirsty fury, and a Slavic annexationist design, which prevailed above all in the peace treaty of 1947, and assumed the sinister shape of "ethnic cleansing". What we can say for sure is that what was achieved - in the most evident way through the inhuman ferocity of the foibe - was one of the barbarities of the past century.

— Italian president Giorgio Napolitano, Rome, 10 February 2007

The Croatian President Stipe Mesić immediately responded in writing, stating that:

It was impossible not to see overt elements of racism, historical revisionism and a desire for political revenge in Napolitano's words. (...) Modern Europe was built on foundations… of which anti-fascism was one of the most important.

— Croatian president Stjepan Mesić, Zagreb, 11 February 2007.

The incident was resolved in a few days after diplomatic contacts between the two presidents at the Italian foreign ministry. On February 14, the Office of the President of Croatia issued a press statement:

The Croatian representative was assured that president Napolitano's speech on the occasion of the remembrance day for Italian WWII victims was in no way intended to cause a controversy regarding Croatia, nor to question the 1947 peace treaties or the Osimo and Rome Accords, nor was it inspired by revanchism or historical revisionism. (...) The explanations were accepted with understanding and they have contributed to overcoming misunderstandings caused by the speech.

— Press statement by the Office of the President of Croatia, Zagreb, 14 February 2007.

In Italy, Law 92 of 30 March 2004 declared February 10 as a Day of Remembrance dedicated to the memory of the victims of Foibe and the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus. The same law created a special medal to be awarded to relatives of the victims:

In February 2012, a photo of Italian troops killing Slovene civilians was shown on public Italian TV as if being the other way round. When historian Alessandra Kersevan, who was a guest, pointed out to the television host Bruno Vespa that the photo depicted the killings of some Slovenes rather than Italians, the host did not apologize. A diplomatic protest followed.

In the media

- Il Cuore nel Pozzo, a 2005 TV movie focusing on the escape of a group of children from Tito's partisans.

- it:Red Land (Red Istria), a 2018 film directed by Maximiliano Hernando Bruno and starring Geraldine Chaplin, Sandra Ceccarelli, and Franco Nero.

- Warlight (Warlight - Michael Ondaatje), a book written by Michael Ondaatje (Jonathan Cape, 2018).